IN THE DAYS OF THE COTTON WIND AND THE SPARROW - EXILE EDITIONS, 2017

A mystical encounter with the allegorical inhabitants of a remote civilization. In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017) is a mystical encounter with the allegorical inhabitants of a remote civilization. A lone chronicler welcomes us into the life of the settlement, and introduces a cast of mythical figures that includes the woman who dissects dreams, the cliff dwellers, and those entrusted with the task of keeping the communal fires burning. This essential landscape is the staging ground for the inner sanctum of our most intimate experience. Through his vivid language and imagery Rafi Aaron creates a compelling poetic odyssey, with a uniquely indigenous voice, that covers vast distances of human and spiritual terrain.

In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017) is a mystical encounter with the allegorical inhabitants of a remote civilization. A lone chronicler welcomes us into the life of the settlement, and introduces a cast of mythical figures that includes the woman who dissects dreams, the cliff dwellers, and those entrusted with the task of keeping the communal fires burning. This essential landscape is the staging ground for the inner sanctum of our most intimate experience. Through his vivid language and imagery Rafi Aaron creates a compelling poetic odyssey, with a uniquely indigenous voice, that covers vast distances of human and spiritual terrain.

Paul Hamann of The New Quarterly notes that, “Rafi Aaron’s poems bask in the ethos of a world of prophets on mountaintops, and stray-travellers-at-your-door, timeless and existing in different incarnations. Everywhere there is the whisper of a teasing seductress, fraught with confusion, sackcloth and uncertainty, and in that whisper you hear the master of the poet’s craft, banishing your thirst for travel beyond the borders of all that you know.”

For the poems in this collection Rafi Aaron received grants and scholarships from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council (OAC), the Banff Centre for the Arts, and OAC Writers Reserve Grants recommended by the following literary magazines and publishers: Brick, Descant, Guernica Editions, and The New Quarterly.

The poem, “They Escaped in the Night” was selected as a finalist in the 2011 Montreal International Poetry Competition, and published in The Global Poetry Anthology (Vehicule Press, 2012). Over the years The New Quarterly has published numerous poems from In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow, and nominated “The Naming of the Well” for the 2014 National Magazine Award for Poetry. Other poems in this book first appeared in Vallum Magazine, and Exile: The Literary Quarterly.

Rafi Aaron has expressed his gratitude to Jeff Bien, who edited In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow; A.F. Moritz, who read the manuscript on a number of occasions; and Don Domanski, who worked on this book with him through the Wired Writing Program at The Banff Centre for the Arts.

READ THE NEW QUARTERLY INTERVIEW WITH PAUL HAMANN!

RAFI AARON REFLECTS ON THE CREATIVE PROCESS, AND WRITING IN THE DAYS OF THE COTTON WIND AND THE SPARROW, IN AN INTERVIEW WITH PAUL HAMANN IN THE NEW QUARTERLY, FALL 2013

To read the full article, click here now.

RA: What is important to me is the advancement of the craft of poetry, how the craft is evolving. My poems make leaps, but in the leaping you’ve got to leave the reader somewhere to take off and land. Sometimes the take-offs and landings are subtle. If you miss them then the poems become…my mother wishes my poetry were simpler. “Why don’t you write poems that are easier to understand?”

PH: (Rafi breaks into a broad smile that has about it a complete absorption in the moment that I wish I could find.)

RA: In a good poem you can’t see the nail holes and seams. You don’t see all this combustion but it sort of comes out of nowhere without all the preamble that even the best writers sometimes get trapped into using. This ball of fire is just tossed effortlessly toward you. I marvel at that.

PH: Do you feel a need to be poetic? Do you ever feel hampered by it?

RA: That’s a great question. It’s something I’ve never really explored. I have a reverence for poetry and sometimes that hampers me. I admire the poets of the past. There are two phases for me when I write. In the creative phase I’m not thinking about devices. The lyricism of my poetry comes naturally to me. Its something that happens intuitively, automatically. If I knew how to do it I’d do more of it. But in this stage I’m not thinking

about accessibility. In the editing stage I try to see what works and doesn’t work. That’s when I check to see if there are enough take-offs and landings for the reader. “89 Clarence Street” went through 69 drafts.

PH: Are there poets who have guided your effort to advance your craft?

RA: I am a Yeats fan. At different times it’s been different poets: the poets writing in Spanish, Octovio Paz, Federico Garcia Lorca, Neruda, and certainly Vallejo. Canadian poets, Irving Layton, Jeff Bien whose work I have helped to edit. I should mention A.M. Klein as an influence on me. We’ve already talked about Milosz and let’s not forget about Rimbaud.

PH: I find that your poems speak so often in metaphors, symbols and silences that when you set those devices aside and speak more literally, there’s a shock. I felt it in the fifth stanza of “The Photograph of the Children:” “one brother arrived in Montreal /the others: sisters parents uncles and aunts / erased the family name /as they walked into the gas chambers.”

RA: Maybe there’ll come a time when I’ll become more literal. In the manuscript that I am currently finishing, I go into a very direct sort of line like the one you just read, after using the metaphorical. Do you follow baseball? (I nod) So you understand pitching. Well, I look on it as my off-speed pitch.

PH: So, you use a metaphor to describe your tendency toward direct, literal language?

RA: Yeah, put that in. That’s hilarious. Sometimes writing poems is like putting something new on a building—an awning over a window or door, perhaps a weather vane on the roof. I’m informing the reader in another way that I haven’t before. If this process continues then maybe there’ll be a new façade on the structure, or even better I’ll have to knock the whole thing down and build something new. In this way the poetry evolves into whatever form it will take.

PH: (Jeff Bien concurs. In a recent letter he described the new direction that he sees Rafi’s work taking: “The splendor of his most recent manuscript lies in its simplicity. In the newest of his poems I hear a deep and enduring silence, amidst the beauty of the lyricism. Rafi has an ear for the occasion, a true singer, in that silence.”)

PH: I was taken with the rhythm of the opening of “What Mandelstam Meant to Russians During the Stalin Years”: “Wait for the night when the half moon swings in a / hammock of purple fog”. Are you conscious of rhythm as a force in your poetry?

RA: It is an element of meaning; it can bring something to life and highlight it.

PH: I’m curious about this highlighting. It seems to imply taking attention away from other things, the things that are not highlighted. In “The Journey” you describe “how I skipped a noun through a /verse, with a strong hand and an arrogant smile.” Is poetry trickery or a pursuit of something noble and permanent?

RA: In certain cases language can reach beyond itself as a medium, and become the things it represents; sometimes not. There are many mountains to climb, many achievements for poetry. Are they all noble and permanent? Good question. Words in poetry have the ability to create some spark, some magic, something they can’t do in any other form. The raw material is words and I prefer to use them in this manner.

PH: I was taken with the rhythm of the opening of “What Mandelstam Meant to Russians During the Stalin Years”: “Wait for the night when the half moon swings in a / hammock of purple fog”. Are you conscious of rhythm as a force in your poetry?

RA: It is an element of meaning; it can bring something to life and highlight it.

PH: I’m curious about this highlighting. It seems to imply taking attention away from other things, the things that are not highlighted. In “The Journey” you describe “how I skipped a noun through a / verse, with a strong hand and an arrogant smile.” Is poetry trickery or a pursuit of something noble and permanent?

RA: In certain cases language can reach beyond itself as a medium, and become the things it represents; sometimes not. There are many mountains to climb, many achievements for poetry. Are they all noble and permanent? Good question. Words in poetry have the ability to create some spark, some magic, something they can’t do in any other form. The raw material is words and I prefer to use them in this manner.

RA: Words have a lot of meanings, and I am concerned that they have become watered down fossils, something different, something less than they were.

PH: Does this make truth a difficult thing to get at? Are the art of writing and the love of truth ever compatible?

RA: I find that the problem of articulation…when you talk about truth, you’re looking at yourself first—all your contradictions and half-truths. I’ve been examining myself for too long.

PH: (Another engaging smile).

SELECTED POEMS

By The Late Night Fire

They told our stories by the late night fire. And we

watched the silent movements that slowed the

onslaught of words: the way an image was

summoned to the mouth or the streams where the

real and imaginary mingled, and where a

trembling finger touches only you.

And we wondered who or what would appear; the

muted thunder calling the rain back to a forgiving

cloud, the leaves of abandoned trees, you and your

beloved and all of summer alive and breathing.

The wind was humming, the clouds shifted, the

chariots of a god barely visible, the nymph

holding the reins and the riding crop high, while

the glazed eye of the moon looked over an empty

battlefield.

Then the long sleeve of the storyteller falling over

his arm, covering our future in sackcloth and

uncertainty. With a walrus’s tooth he ripped

words open. The tale had begun, the slaying of

truth, echoes surrounding us, and laughter stood,

motionless, in the valley.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

Autumn Knew No Mercy

Autumn knew no mercy. It encircled us from the

east and the west forcing us to look at an angry

sky.

The shoulders that once carried dreams sloped

forward and revenge crawled in the vineyards and

abandoned gardens.

The words for ‘sun’, ‘breeze’ and ‘warmth’ now

covered in mud, trampled by the slow-moving feet

of mules, and the cry from the deepest canyon was

your own voice mourning a lost season.

Provisions were hoarded (winter always overstayed

its welcome). The storytellers sharpening their

tongues for the long nights ahead, carefully

concealing words and snaring the warmth of

summer.

Finally what one remembers is the same in every

season: the fishermen lashing their prayers to the

old boats, and the widows huddled together,

counting whatever it was they counted.

And as the vision of the elder, asleep for so long,

awoke in our hearts, we talked of burning the outer

ring of fields, so the foot of disease would be

cloaked in ash as it wandered nearby.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

After the Harvest

After the harvest the fear of storm clouds floated

away. The besieged ponds and lily pads eyeing

their shadows. Another day weakened from the

weight of the sun resting on the river. In the

clearing, united under one banner, the battle with

weariness raged. No one stirred to tend the sick.

Love strayed into the unforgiving house of sleep,

the heart its own hand, overused and calloused.

And the coarse words of the whalers’ song

whispered like a lullaby, and nothing wakes you;

not the creaking door opening the dream or the

crowd of fears gathered around winter. And we

sailed on one thought: May the river never open

its toothless mouth to flood the fields where I have

laboured.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

The Marauders

They came out of nowhere, from under a rock,

or the melody of the bluebird.

They came with white shadows in their eyes.

They came leaping over all the summers, and the

sighs of lovers.

They came with their daggers, in a bone-cracking night

carving the youth out of every man.

And lifting the weight of my fear I severed the

head of this day.

And in the fields a torn dress, hanging on the

naked branches, waiting for the girl who had

already begun her journey.

Yes, they came like the children running through

summer to this shallow place where everything

surrenders.

The lips tremble searching for that sound

the living cannot make.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

The Plowing Hand

And the stars burst and the heavens, some say,

refused to open.

In the window all is light, all is not forgiven.

Revenge reaches for a weapon, the sharpened

stone that knows only the smallest veins.

You wander down ancient steps to where your

siblings bathed and watch your thoughts sail in

the same waters. The river speaks in tongues to

ostracized petals, wind-ripped weeds and the red

fin that silvers the night.

And you plead for something other than what we

constructed from twigs and sharp words,

something other than the plowing hand sowing

vengeance into the land.

A stray traveler arrives at your door speaking a

different language and you understand what you

see; day-old hunger grooming the face of fear.

The moment contracts, the memory expands. The

remaining stars abandon their positions and leave

for home, or another sky.

And you see the couple who swallow the

forbidden egg, then turn blue and shining,

a thought wandering in the clouds.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow

In the days of the cotton wind and the sparrow the

ponds refused to ripple. The memory of floods

carried us away and the sweet taste of water

stained our tongues. Some sought out caves,

others lay down in dugouts and covered

themselves with straw. And so it was with us. I

remember lying there with her, a bud of youth

spring had almost forgotten. We wandered into

the three forests of no return; the glance that sees

all, the smell that harnesses a fever to the blood,

and finally the first touch sealing one fate to

another. And although eternity was far away I

knew I would live forever in this moment.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

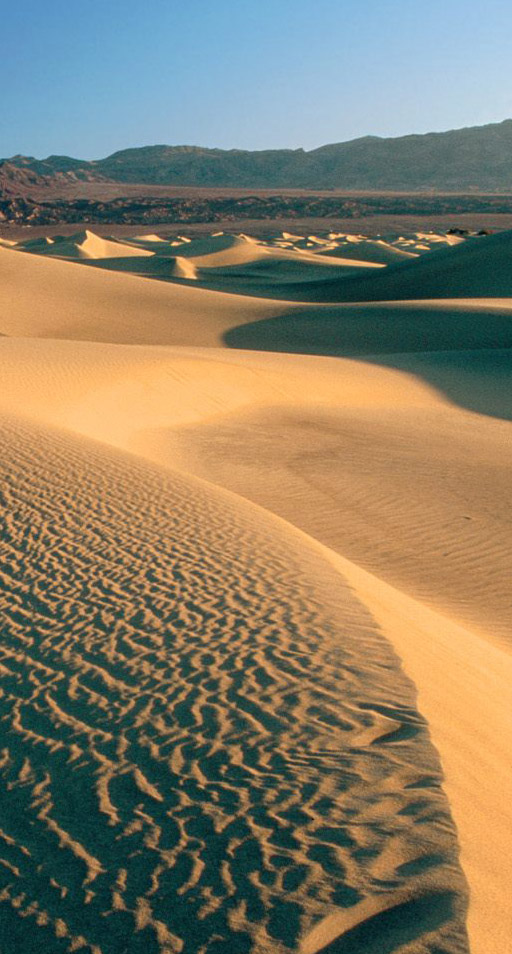

The Naming of the Well

For Jeff Bien

Who names the well? Anyone who has carried thirst.

The summer well, that speaks to you in violet and

apricot, and the staggering well that falls on its

knees before you, breathless with its agony.

The emancipated well shouting “freedom” into

the whirling sands, and then closing its mouth,

forever.

The star-coloured well that sent you dreaming

when your tongue lashed its cool waters. And the

strangled well, filled with white venom.

The relentless well pursuing you through deserts,

villainous swamps and the long border of your

day.

The flamboyant well, with its cape of painful

colours, reminding you of stretched limbs and

burned skin.

And the prophetic well that tells you what you

already know; “tribes and herds will die from this

water.”

The scar-faced well with her magnificent, impish

eyes, that you now call naked blue.

The cursed well and the one that curses, the flying

well that soars above you, its feathers softening

the sun.

Well with the silk lips of the wind and the long

black strands, that bored itself into your heart

spring and filled with red waters.

The makeshift well that is a meeting place and a

stone mouth.

The royal well, the fountain of forever within you.

All wells are childish playing with your image of

taste and tongue, monastic, and overwhelmed,

thinking of those outstretched hands.

The infant well that cannot speak the name of

mother water. And the old well recounting how its

streams were once sweet and now spittle between

missing teeth.

The pious well, prostrate before you, praying for

rain. And the salacious well that invites you in

while the others are out in the fields.

The right sided well and the left, tossing

something down your throat, a twig, a granule of

sand, or a misused word. And the middle well no

one drank from, (or should I say trusted.)

The coy well, some water some of the time.

The outcast well no one has seen for years.

And the ancient well, where one navigates the

rope the way you would a great mystery.

In the underbrush and the bramble, a petal of a

flower, lifeless, and sleeping, in the taste of late

night visitors that somehow banished your thirst.

You see this and ask, “How many days walk, how

many sunsets will come and go before the naming

of the well?” And there is no answer, only a

breeze that bruises your lips.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

The Hunting Party

I remember how rivers swelled and the blood

flowed from a red tourniquet tied tight around the

pale white sky. Soon the hunters would head into

the forest. These were nights of sleeplessness, the

wild boar, and the one long tooth of the tiger

devouring dreams. These were also the nights of

forgiving love, where a woman braided years of

passion into a keepsake that waved like wild grass

at the entrance of the heart. The feast began. The

fires were lit to the eye of the Watchful One who

would lead the weary home. No one ate well. Our

thoughts were in the deepest part of the forest, that

place where tall vines strangle the uncharted years

and the husk of a single word wounds the tongue.

Yes, death was calling, it was the same dark sound

we knew but never named, the same silence night

plunges into the back of the retreating light.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

After The Deluge

After the deluge water hammers surrendered. A

rainbow, washed out and white, hung in the

southern sky.

A bird tried to speak. No one wasted words. And

prayers that never wandered beyond the mouth

stood up reaching for their sound.

I heard the moaning of riverbeds and roots that had

been dragged away, and the strong arm of the

wind lifting the fragrance of frail colours in their

final hours.

After the deluge the kneeling, bowing and placing

of a cheek into the muck. And by the river, waves

sleeping with their heads on the shore.

Morning came with darkness and unsatisfactory

blue. We searched for food and I bit into a

childhood story savouring the salt that preserved

my youth.

The song of the earth rose from subterranean

gardens. Men buried their tears and danced the

dance of joy, all of us children, with clay on our

feet and innocence in our eyes.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

At the Desert’s Open Door

The story began, as it always seems to without

warning. Suddenly wandering through the

bush or the plains, we begged for the fire,

cinnamon-laced flowers, a night palace staged

at the desert’s open door, where every star was

accounted for, and the laughter that feeds

laughter.

On the other side of the woods the name-calling

– the red spruce shouting at the goldfinch –

and the wild grass demanding the stray hoof

of any beast flatten its tangled hair.

You imagine warmth, the victorious ray of

sunlight on the high ground above the hills,

and the skin of glass igniting the bones, the

downpour of sweat sweeter than honey.

Even in your sleep your thoughts are travelling

knee-deep in the sand. You wonder how long

it will take – this journey that leads you on –

how many stories will be severed from their

endless endings, and leave you to resurrect the

shards of a dream.

You start with what you know, the Noble Tent

– a place of worship; two watchtowers – the

steel eyes of the settlement, and then the

savage pit where more than one body lies.

In the coming months a silence, so green,

grows in the deepest canyons. Then and there

you witness the ancient rivalry – the silver

pincers surprising the sleeping darkness and

the malicious sound of the inconceivable that

refuses to leave your ears. And the black

feathers fall.

© Rafi Aaron, In the Days of the Cotton Wind and the Sparrow (Exile Editions, 2017)

They Disappeared in the Night

They disappeared in the night as the white ash of

the fire went cold. They disappeared with the tales

the almond tree had overheard. Only the stray

mountain goat and the restless stones that

wandered with our people for years knew their

story.

You must understand they left us the way a leper

leaves you living in the weak house of your skin.

It was late in the life of spring how could this

happen?

We searched for signs; a feather from a striped

bird, or the fruit of the peach tree wearing the skin

of the elders. Who would lead us now? The voice

of reason was dead and still dying as we argued

into the next day.

Then the old woman spoke: A nightingale is only a

nightingale when it confesses its brightest colours

are hidden in its throat, and a dog becomes the

animal we know when it pulls love out of the

master’s hand.

And as the mangled tree straightened a branch our

tongues curled and no one spoke. And the silence

fell, and it fell like a man falling off a cliff without

having one moment to shout out his name, only the

silence filling his body, then the gorge, then the

lives of all who knew him. This was the traveling

silence, the twin of sorrow that knocks on every

door and never tires.